Seeking roots: Abed Al Kadiri’s The Blacksmith and the Rubber Tree

Commissioned by Sursock Museum on the occasion of Abed Al Kadiri's solo exhibition, The Story of the Rubber Tree, 2018, this text explores Al Kadiri's interest in the relationship between personal memory and the intimate fabric of the city, through the history of the rubber tree in Beirut.

Down Zaroub Abla in Aicha Bakkar, Abed Al Kadiri finds the 80 year-old house his father grew up in. Sprawling through its garden is a huge tree. Not the fig or mulberry tree he heard about in stories told to him in childhood, but a rubber tree, vast and wide. Impervious to weather, its matte, flat leaves are waxen and sturdy, and cleaved in two, like palms held open, as though each made to hold a book.

For Al Kadiri, this house has lived as fiction: a once-utopic familial home now the half-abandoned source of a violent fraternal rift. Upon the death of his grandfather, who built the house, his father and uncle could not agree on who should own it, nor how to split and manage the assets its inheritance represented. They fell out irrevocably, and have not spoken since. The rift has coloured decades of family history. On the day Al Kadiri stood in the garden, he understood the enormous rubber tree to be the only true witness to the house’s history. In the same eerie way in which you learn a new word and start hearing it everywhere, overnight Al Kadiri began to see rubber trees across the city. Overspilling gardens, bursting through ceilings, overhanging the pavement: each signalled a Beiruti house abandoned, and – behind the house – a family no longer living in it.

It is hard to know how rubber trees first came to Beirut. The Brazilian Emperor visited the Ottoman Lebanese territory in 1877, and migration to Brazil by Lebanese began in earnest afterwards. Rubber trees are native to South America, perhaps one was brought over as a gift to the local Ottoman governorate. They feature in a book about Egypt from the late nineteenth century, where they are known as a ‘tree of shade’. However they arrived in Lebanon, by the 1930s and 1940s rubber trees were being planted for precisely that reason: quick-growing and wide, with dense foliage, they were excellent wind-breakers and sun-shades for those building houses along the capital’s coast.

The first painting in Al Kadiri’s series The Blacksmith and the Rubber Tree (2017-18) imagines a scenario just like this. The sun streams through a few clouds over the quiet sea, as a man plants a rubber tree sapling in the ground of his young garden. A simple wooden fence delineates the lawn from the world beyond, to which the man has his back. On the other side of the fence another tree grows: skinny, dark and leafless, its bare trunk a counterpart to the vivid solidity of the nascent rubber tree. Across the page – each painting operates as diptych – a slender house, freshly-plastered, takes up most of the image. Modest in scale, the house features details of late Ottoman architectural vernacular: arched doors with external shutters, a simple curlicued balustrade and lattice-worked windows. Here the wooden fence runs along the front of the picture, separating the viewer from the house, concealing its entrance. Another stark, plain tree appears here too, locked out of the gated plot, as though to emphasise the fresh fertility of the environment being built within.

An American encyclopaedia published in 1846 credits the caoutchouc, or rubber tree, with an average growth of 25 feet in just four years, its trunk reaching four feet wide. Yet those who originally planted the tree for shade had no idea the damage it could inflict upon their homes. The faster and wider its branches grow above ground, the swifter its roots spread below it. Rubber trees ravage and infiltrate the foundations of houses, and undermine the structural integrity of buildings. For anyone who continues to keep rubber trees, therefore, maintaining and controlling their growth is imperative. The wild and unlimited presence of a rubber tree is today a sign of abandonment, a marker of absence, of no-one around to keep it in check. Once rubber trees begin growing, it’s hard to stop them. People speak of ripping up their floorboards to pour petrol on bare roots, of burning the trunk.

The second panel in Al Kadiri’s series reveals the man who planted the tree to be a blacksmith, toiling over the anvil in his workshop. We’ve moved inside the house, and so has the tree. Decades have passed. Faint sketches of the house are still visible on the right, but they feel abstract and disconnected, barely perceptible behind the tree’s bulk. The sapling is now large and heavy, with three arterial branches unfolding from the central trunk. Thick vines, like sheets of running water, fall from them; the tree’s roots descend into dense smudges of ink. A couple of the outermost branches transgress the boundaries of their painted page, stretching into the space of the blacksmith. He remains oblivious to its presence, and works on.

Civil wars are particularly pernicious conflicts, because once they end their participants have to live side-by-side with those previously designated the enemy. Civil war erodes trust between cousins, friends, and neighbours; it fractures the ability of a generation to be generous to one another. Without public ‘victory’ to mark an ending, or the total withdrawal of an adversary other, civil war makes closure almost impossible. It also tends to have socioeconomic consequences, as destroyed land and abandoned housing offer corporate real-estate developers the opportunity to rebuild at profit. Civil war in Lebanon changed the spatial, cartographic nature of the city, and also crucially altered the political structure through which Beirut was managed and developed.

The 1990s ushered in a new era of privatisation of public space, and political corruption was mirrored in architectural ideology. Anything that existed before or during the war needed cleansing and renovation. The destruction of historic neighbourhoods became part of a discourse of regeneration; its rhetoric masked the violence of the erasure of collective memory. Today the government continues to use high taxation as an incentive for owners to destroy old buildings, sell the land and facilitate the construction of elite real estate by developers. The law renders it no longer in an owner’s interest to renovate or preserve an old building.

At the same time, inheritance laws mean families find themselves locked in complex battles over land. This predominantly affects brothers. Lebanese personal status legislation makes clear that sons and daughters should inherit property equally, and a Succession Law has existed since 1959. However, despite stipulating that gender and religious distinctions be no barrier to inheritance, the latter law only applies to non-Muslims. Muslims are governed by judiciary codes that are weighted in men’s favour, and many women – particularly Palestinians, or those married to foreigners –are denied the right to inherit marital property or their equal share of it. Though not uniquely an issue among men, the animosity that surrounds property inheritance has, judicially at least, a peculiarly fraternal quality.

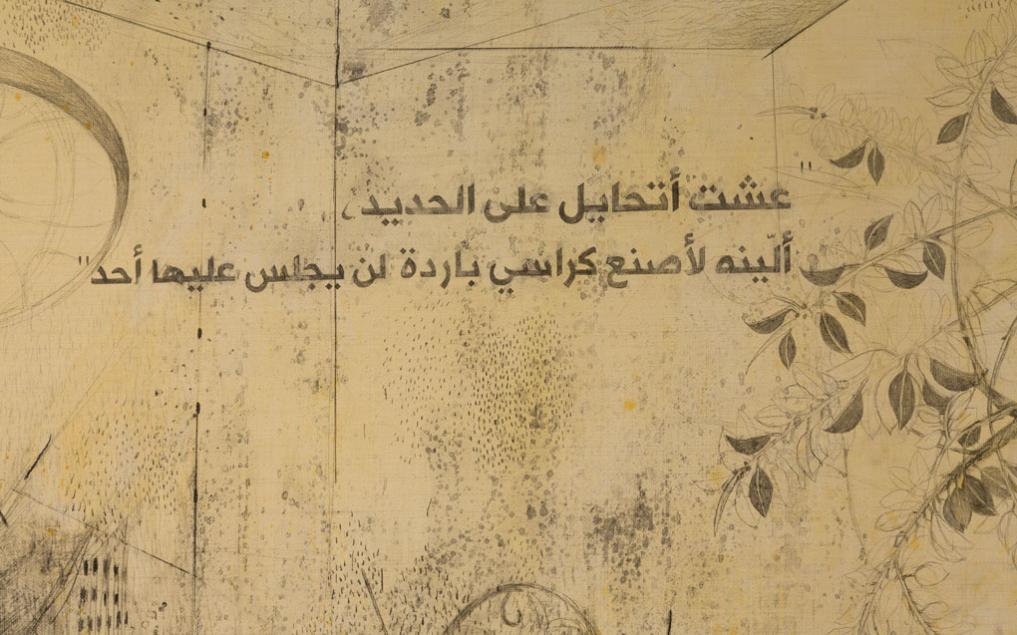

The third panel in Al Kadiri’s series hints at this strife. The “page” has yellowed, wrinkled with the stippled fur that mottles old paper. We’re in the post-war years, the blacksmith is dead. His studio now is empty of tools, it has become a cluttered storeroom for piles of cast-iron chairs, cold and forgotten. The rubber tree has grown unabated, expanded steadily to fill the frame of its image, and burst across the seams. A small port-hole at the back of the workshop peeks on to the garden on the other side of the house. Rubber leaves are visible through it – the tree has the house surrounded.

Today, the rubber tree has emerged as a useful weapon in the quick sale of property; an instrument of violence. Its fast-spreading roots can undermine a building’s foundations in just a few years, allowing owners to label an old property derelict, and pursue its sale. Planted originally for citizens seeking to put down roots, the tree ends up becoming a sign of their erosion, destroying the foundations of buildings and reflecting the fracture of families supposed to live within them. Al Kadiri’s paintings chart the dissolution of a Lebanese dream, without becoming complicit in its fiction. The utopia of the 1940s, in which a blacksmith can afford to build a house and urban garden on the waterfront of Ain el-Mreisseh, is tempered by the image of the consistent manual labor that made it possible. In the final image the product of that work is all that’s left: a tangled stack of chairs that no-one sits on. The house is not occupied by those whose legacy it was intended to constitute; in fact the man’s family never appear at all.

Abed Al Kadiri’s work uses the rubber tree as a vehicle for a deeply personal story. In seeking to understand the source of a feud between brothers, he returns to the house they were born in. The house forces him to reckon with its origins, the hopes it represented, and the eventual dissolution of its optimism. Exploring these requires navigating realities of the war, of the city, and of the law. The rubber tree is more than a metaphor in this unfolding, but a literal marker of time’s passing, a physical mirror to changing geopolitical dynamics. The work stems from the effects such changes have upon the individual, but the rubber tree remains invulnerable throughout, an ominous monument to kinship unravelled.

Al Kadiri’s meticulous drawings mark a departure from his existing painting practice. His earlier work, freer in style, is equally invested in understanding contemporary political realities through the lens of historical references – the Maqamat of Al-Wasiti is the source of one of Al Kadiri’s most powerful bodies of work. The Blacksmith and the Rubber Tree (2017-18) consciously references the engravings and watercolours that hang in Lebanese houses today: of perfect, historic Ottoman-style homes, of a ‘golden age’ when Beirut was the Paris of the Middle East, and Lebanon its Switzerland. Al Kadiri’s images recognise the blinkered perspective such nostalgia requires. The book is the framework for his narrative, but its form feels closer to the fairytale – visual, linear, poetic – than an authoritative historical text. Pencil and graphite, after all, are provisional mediums, they smudge and fade, intended as the foundation for a painting yet to come. The work dwells in the world of the sketch, the unfinished; as though aware that seeking roots involves making fiction.

- Rachel Dedman