Published here with Culture+Conflict and here by ArtDiscover

The exhibition #withoutwords at P21 gallery in London is committed to exploring and honouring the multi-faceted work that has emerged from Syria in its years of recent conflict.

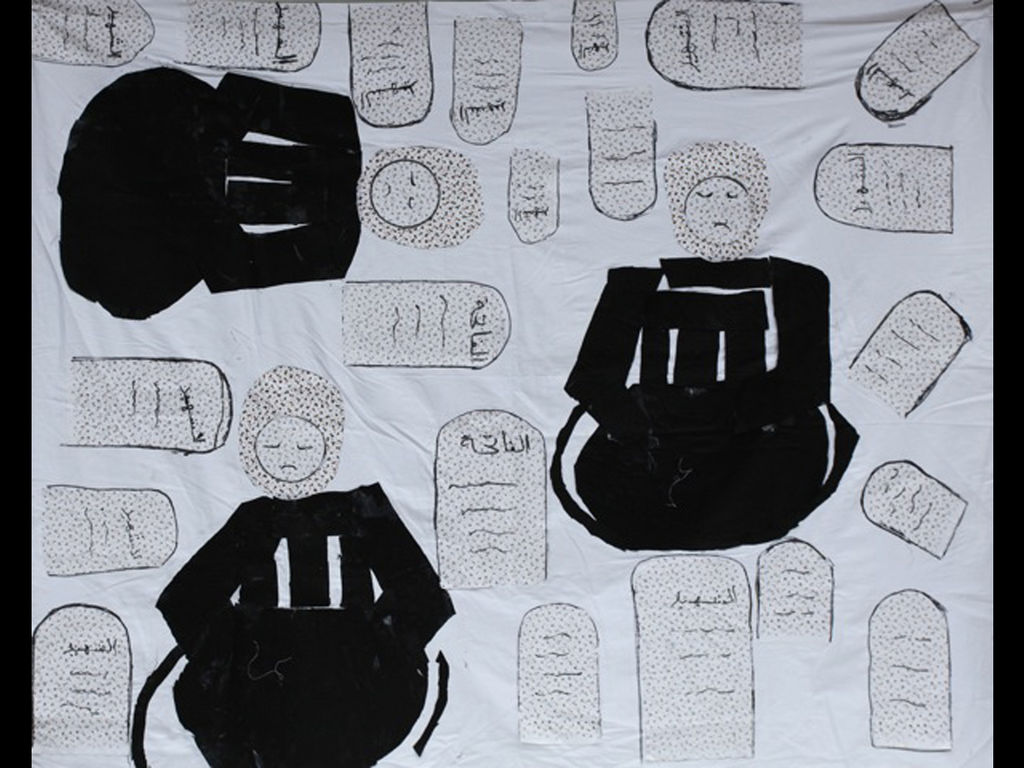

The first piece I came across was intensely moving in its simplicity, the product of art workshops run by artist Hazar Bakbachi-Henriot for Syrian refugee women in a Turkish camp. A simple wall-hanging they produced is shown here; patches of fabric collaged onto a thin sheet. Swathes of black cotton construct the basic iconography of three women, whose bodies exude both domestic solidity and mournful emptiness. Floral cloth denotes their scarved heads, and scraps of the same flowery fabric surround the women in the form of gravestones. This double use of the material is key to the work’s impact, connecting human loss to maternal grief. Adrift on the white background, in an endless abstract cemetery, the women’s pain and person are subtly mirrored, swimming in the same sea. To distinguish visually between the women’s skin and their headscarves, the floral fabric has been layered: round moons have been cut from the middle and inverted, to make faces. The weft of this cotton is paler than its warp, the flowers faded and ghostly. The material loses its textilic quality, serving instead as skin drained of colour, literally turned inward: reflective, bereft.

Though made by seventeen women of different ages, for its creators the piece surely serves as a kind of self-portrait. Do the female figures represent the universal grief of mother, sister, daughter? Or are the women swathed in anonymity, stripped of identity in the face of death in such volume? The questions this ambiguity raises in part generate its emotive content. Woman and victim, life and death, are literally cut from the same cloth. In places home-made glue seeps round the edges of the material, and the marker pen used on the gravestones is still roughly visible where they have been cut. The piece’s construction echoes the emotional fabric of its makers – far from home, surrounded by absence, rendered raw and unhemmed.

At the other end of the exhibition was creative youth collective Waw al-Wasel’s work Al-Bastar, or The Boot, a film that takes a remix by Omar Suleiman of Bjork’s song Crystalline and sets it to visuals of the Syrian conflict. The artist has taken footage from YouTube of both regime forces and the Free Syrian Army and subjected them to the graphic tricks and digital manipulation predominant in convential music videos: split-screens, mirrored images, clips shown at hyper-speed. The former march and swing their boots, jump into their jets and push bombs from planes. The latter crouch on cars with anti-aircraft guns, stalk the streets and sling arms round one another in makeshift barracks. The absurdity of the manipulation can be comically surreal: a clip showing soldiers raising their guns above their heads is run back and forth like a yoyo, so that the men appear to wave their weapons in the air in time to the beat of Bjork’s voice. The song’s consistent bass is overlaid by a montage of real-life car bombings; the tin of its tune augmented by staccato gunfire, carefully matched to the score.

This approach constitutes a kind of iconography, rendering the filmic material complicit with the commercial, superficial, manufactured visuality of the popular music industry. The film powerfully intimates the senselessness of the conflict; both sides are made ridiculous. It comments on the mass reception and understanding of war: disseminated through multiple media lenses, the broad global public imbibes a view of the struggle so detached from the bloody reality that here it descends into farce.

Waw al-Wasel’s provocative, tongue-in-cheek commentary on the performative fallacy of contemporary civil war couldn’t be more different to the quiet, dignified collage of the women working under Bakbachi-Henriot’s guidance. And yet, both pieces make use of contemporary public material. One comprises cheap cotton fabric and home-made glue, the other crowdsourced imagery from the shared landscape of the internet. Al-Bastar employs dark comedy, the wall-hanging a basic, guttural grief; and yet together they speak to the irrationality and sadness that are the uncomfortable bedfellows of civil war. Crucially, both pieces are created as part of a collective. Whether informal in diaspora, or an established web-based project, both promote artistic collaboration in the face of human trauma. It is this breadth and inclusivity that makes the exhibition unusual, striking and a moving reflection of contemporary Syrian feeling, and approaches to creative practice. The exhibition may be without words, but its work is not without voice.

The exhibition was a joint initiative between P21 and the charity Mosaic Syria. It ran in the Summer of 2013, in London.