Note from Beirut: on growth and abandon

Commissioned by La belle revue as part of their Global Terroir series, 2019.

For the last few years, I have worked from a small room at the top of an old house in Zoqaq el-Blatt, Beirut. The room isn’t original to the building, from the outside it looks like a narrow tower jutting up from the left wing. You can see the sea from my desk, a little slice between skyscrapers. The room is pretty high up, three or four storeys, but my sense of height is skewed by the view from the balcony. Skimming the cast-iron railing are the branches of a rubber tree, as big as the house, as wide as it’s tall, vast and impervious. Its matte, flat leaves are waxen and sturdy, each cleaved in two, like supplicating palms.

The rubber tree—caoutchouc—seems sprawling and innocuous in the way that natural things do, but is actually a marker of precise historical and contemporary conditions. Abed al-Kadiri’s triptych of paintings The Blacksmith and the Rubber Tree (2018) locates the rubber tree’s introduction to Lebanon in a moment of late-Ottoman prosperity, a time when blacksmiths, carpenters and other labourers could afford to build comfortable houses for their families along the Beirut coastline—a stretch of real estate worth millions of dollars today. Young families would install rubber trees as quick-growing sources of shade for their gardens, and Al-Kadiri’s first painting imagines this scene as one of noble euphoria: a man plants a rubber tree outside his young house, on the shore of Ain el-Mreisseh, sun shining on his toil.

![Abed Al-Kadiri, The Blacksmith and the Rubber Tree, 2017-18]()

Unbeknownst to most, however, the faster and wider rubber trees grow above ground, the swifter their roots spread below it, destroying the foundations of buildings. Like storyboard stills, Al-Kadiri’s paintings move with progressive intimacy inside the house; time goes by and the surface of the canvas mottles, the brightness of the fable fades, the paintings darken, neglect sets in and the tree runs wild. The demise of the Lebanese working-class dream is underscored by the naivety of the gardener; Beirut’s history—the fall of the Ottoman empire, colonial mandate, civil war—is subtext to the tree’s metastasising. Once emblematic of the labour and leisure fundamental to modest aspiration, the tree’s unlimited growth becomes a sign of abandon, a marker of absence. Rubber trees can become almost impossible to control; people speak of ripping up their floorboards to pour petrol on bare roots, of burning the trunk.

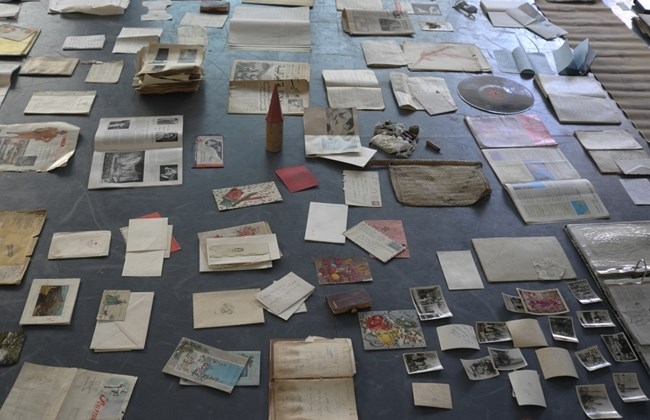

The rubber tree at the balcony window is planted in the courtyard of an abandoned building, once very grand, just over the road. No one lives there now, the roof is lost and only the main arterial walls and floors remain. It is one of hundreds of abandoned buildings in the city that Gregory Buchakjian has for years documented through photography, film, and the collection of objects. His work was shown recently at Sursock Museum, Beirut, in the same space Al-Kadiri showed his paintings six months earlier. In one room was a bureau of index cards, one for each abandoned dwelling, arranged by neighbourhood in stiff catalogue. In the other was a video in which Buchakjian and his colleague laid the objects they had gathered from old buildings in rows on the floor. They described the items as they held them, let the camera linger on old books, lost toys, anonymous photographs, lace collars, a bloodstained ammunition belt, reading out loud from letters and postcards, overlapping scraps of narrative.

![Gregory Buchakjian and Valerie Cachard, Abandoned Dwellings. Archive, 2018]()

Al-Kadiri’s and Buchakjian’s work intertwine the fictional and anthropological as approaches to lived history, and reflect local concern in artistic practice for connection between the material fabric of the city and the emotional stuff of memory; the reading of socio-political events through things left behind in old houses. Sometimes it feels too easy to draw on the ready history of such places, the literalness of their connection to the past threatens to fetishise them, and invest the dust-choked items inside with totemic significance. Other times it seems fitting that the anonymous intimacy of an everyday object—sign of lived time, of someone here, then—holds the starkest mirror to the relentless obliteration wrought by land speculation in Beirut, which destroys historic buildings, people’s homes, and architectural heritage, to build bleak high-rises nobody can afford.

For years, Ghassan Maasri would walk around Beirut and enter abandoned houses that hadn’t yet been torn down or sold. With those that seemed structurally sound, he’d track down the owners, mostly coming up against suspicion, lawyers, or four decades of family property disputes. As property prices rocket in Beirut, many people who own old buildings wish to sell, and the government offers tax incentives to bolster the property market, and the coffers of politician-owned construction companies. For landlords whose houses are listed as heritage sites, preventing their sale to developers, a strategically-planted rubber tree can destroy the house’s structural integrity within ten years. Others arrange to have their property illegally bulldozed in the middle of the night. Ghassan eventually managed to meet the owner of a yellow house on Abdelkader street, with a little room on its roof and a rubber tree over the road. It sits just up from Burj el-Murr, the unfinished tower and anti-monument of the civil war. The house was empty and half-derelict; Ghassan convinced the owner to let him take it over for a few years, to renovate it with a group of artists, designers and architects, to convert its rooms into studios, and its vaulted halls into public spaces.

![Mansion, Beirut, photograph by Christian Moussa]()

Since 2012, Mansion (as the house became) has been conscientiously renovated and animated by its inhabitants and visitors. It is an experiment in shared dwelling and collective responsibility, offering low-cost studios to those who would otherwise struggle to work creatively and independently in the city, and run by an elastic collective of artists, architects, anthropologists, activists, curators, playwrights and bike-messengers. Mansion’s community maintains Mansion’s public spaces: the library, film archive, silk-screen studio, sound space, dance studio, hot desks, internet connection, kitchen and garden, while navigating the politics of living and working together. The house hosts exhibitions, meetings, talks, performances, residencies, screenings and events, as well as innumerable invisible processes and practices—relationships, collaborations, conversations. Mansion is a conscious response to the dominant impulses of Beirut’s postwar reconstruction, an attempt to reclaim ‘failed’ sites for new practices of habitation, encounter, and production.

![Image from the Civil Campaign to Protect the Dalieh of Raouche]()

One project connected to Mansion brings together political, legal and artistic responses to the systematic erasure of one of the last remaining pieces of public coast in Beirut. The modest house on the coast in Al-Kadiri’s utopic first painting is long gone now, its lost foundations dwarfed by beach-front resorts. Amid exclusive yacht clubs and overpriced restaurants, the rocky stretch of the Dalieh of Raouché remains a place where fishermen live, families meet, and children learn to swim. Despite public access to the sea being enshrined in Lebanese law, the government has systematically sold Dalieh off for development—a mega-hotel is set to be designed on the site by Rem Koolhaas. The Dalieh Campaign, Public Works Studio and Temporary Art Platform have launched juridical, political, intellectual and creative challenges to this destruction, the latter taking the form of commissioned artist interventions along the coast. Ieva Saudargaité’s Thin White Line (2017) divided Dalieh in two with a 400-metre stroke of chalk. Derived from limestone, of the kind found on Dalieh’s rocky landscape and used in the construction industry to produce mortar, the line reflected the site’s legal designations: on one side, land protected from construction; one the other, land that can legally be built upon. Left to the mercy of the sea and rain, the line got bleached, blurred, washed away. Upset by the very elements its jurisdiction is meant to protect, the work revealed public space in Lebanon as inherently vulnerable, its erasure inevitable, and indelibly tied to speculative construction.

![]()

![Ieva Saudargaité, Thin White Line, 2017]()

Local speculation maps visibly onto the art world, as Beirut’s small and resilient art scene—characterised by a richness of grassroots organisations established since the 1990s—finds its topology changed by a recent rash of private art foundations and large-scale museums. These exacerbate a stifling economic and political environment for the arts, in which funding is exhausted, and mobility limited. Crucially, therefore, at the core of Mansion’s financial model is the gift. The house is given to its community for free, low studio rents cover its running costs, and contribute to residencies and repairs. This gift, although temporary, relieves Mansion from the permanent precarity and unceasing labour of cyclical funding applications, and from the need to conform to narrow notions of institutional success. Remaining independent of art grant ideology, accountable instead to its users and community, keeps Mansion elastic, self-critical, and responsive to the immediacy of its social and political context.

As I write this, Mansion is going through change, an extended period of evaluating its work, questioning its purpose, speculating upon its future, consulting its community and proposing new modes of collectivity and governance. The owner could choose to sell his house next year. Such a scenario would be a significant loss, but I reckon it would also reveal Mansion for what it really is: not a building, but a network of people, who have treated collectivity as a practice, and trained that muscle in themselves. Work though it does for the protection of nature and heritage, Mansion’s greatest assets are arguably most fundamental to the future of nimble, critical cultural practice in Beirut: the space to fail, to change course, to grow with abandon, and to pull up your roots and set fire to them.

- Rachel Dedman

The rubber tree—caoutchouc—seems sprawling and innocuous in the way that natural things do, but is actually a marker of precise historical and contemporary conditions. Abed al-Kadiri’s triptych of paintings The Blacksmith and the Rubber Tree (2018) locates the rubber tree’s introduction to Lebanon in a moment of late-Ottoman prosperity, a time when blacksmiths, carpenters and other labourers could afford to build comfortable houses for their families along the Beirut coastline—a stretch of real estate worth millions of dollars today. Young families would install rubber trees as quick-growing sources of shade for their gardens, and Al-Kadiri’s first painting imagines this scene as one of noble euphoria: a man plants a rubber tree outside his young house, on the shore of Ain el-Mreisseh, sun shining on his toil.

Unbeknownst to most, however, the faster and wider rubber trees grow above ground, the swifter their roots spread below it, destroying the foundations of buildings. Like storyboard stills, Al-Kadiri’s paintings move with progressive intimacy inside the house; time goes by and the surface of the canvas mottles, the brightness of the fable fades, the paintings darken, neglect sets in and the tree runs wild. The demise of the Lebanese working-class dream is underscored by the naivety of the gardener; Beirut’s history—the fall of the Ottoman empire, colonial mandate, civil war—is subtext to the tree’s metastasising. Once emblematic of the labour and leisure fundamental to modest aspiration, the tree’s unlimited growth becomes a sign of abandon, a marker of absence. Rubber trees can become almost impossible to control; people speak of ripping up their floorboards to pour petrol on bare roots, of burning the trunk.

The rubber tree at the balcony window is planted in the courtyard of an abandoned building, once very grand, just over the road. No one lives there now, the roof is lost and only the main arterial walls and floors remain. It is one of hundreds of abandoned buildings in the city that Gregory Buchakjian has for years documented through photography, film, and the collection of objects. His work was shown recently at Sursock Museum, Beirut, in the same space Al-Kadiri showed his paintings six months earlier. In one room was a bureau of index cards, one for each abandoned dwelling, arranged by neighbourhood in stiff catalogue. In the other was a video in which Buchakjian and his colleague laid the objects they had gathered from old buildings in rows on the floor. They described the items as they held them, let the camera linger on old books, lost toys, anonymous photographs, lace collars, a bloodstained ammunition belt, reading out loud from letters and postcards, overlapping scraps of narrative.

Al-Kadiri’s and Buchakjian’s work intertwine the fictional and anthropological as approaches to lived history, and reflect local concern in artistic practice for connection between the material fabric of the city and the emotional stuff of memory; the reading of socio-political events through things left behind in old houses. Sometimes it feels too easy to draw on the ready history of such places, the literalness of their connection to the past threatens to fetishise them, and invest the dust-choked items inside with totemic significance. Other times it seems fitting that the anonymous intimacy of an everyday object—sign of lived time, of someone here, then—holds the starkest mirror to the relentless obliteration wrought by land speculation in Beirut, which destroys historic buildings, people’s homes, and architectural heritage, to build bleak high-rises nobody can afford.

For years, Ghassan Maasri would walk around Beirut and enter abandoned houses that hadn’t yet been torn down or sold. With those that seemed structurally sound, he’d track down the owners, mostly coming up against suspicion, lawyers, or four decades of family property disputes. As property prices rocket in Beirut, many people who own old buildings wish to sell, and the government offers tax incentives to bolster the property market, and the coffers of politician-owned construction companies. For landlords whose houses are listed as heritage sites, preventing their sale to developers, a strategically-planted rubber tree can destroy the house’s structural integrity within ten years. Others arrange to have their property illegally bulldozed in the middle of the night. Ghassan eventually managed to meet the owner of a yellow house on Abdelkader street, with a little room on its roof and a rubber tree over the road. It sits just up from Burj el-Murr, the unfinished tower and anti-monument of the civil war. The house was empty and half-derelict; Ghassan convinced the owner to let him take it over for a few years, to renovate it with a group of artists, designers and architects, to convert its rooms into studios, and its vaulted halls into public spaces.

Since 2012, Mansion (as the house became) has been conscientiously renovated and animated by its inhabitants and visitors. It is an experiment in shared dwelling and collective responsibility, offering low-cost studios to those who would otherwise struggle to work creatively and independently in the city, and run by an elastic collective of artists, architects, anthropologists, activists, curators, playwrights and bike-messengers. Mansion’s community maintains Mansion’s public spaces: the library, film archive, silk-screen studio, sound space, dance studio, hot desks, internet connection, kitchen and garden, while navigating the politics of living and working together. The house hosts exhibitions, meetings, talks, performances, residencies, screenings and events, as well as innumerable invisible processes and practices—relationships, collaborations, conversations. Mansion is a conscious response to the dominant impulses of Beirut’s postwar reconstruction, an attempt to reclaim ‘failed’ sites for new practices of habitation, encounter, and production.

One project connected to Mansion brings together political, legal and artistic responses to the systematic erasure of one of the last remaining pieces of public coast in Beirut. The modest house on the coast in Al-Kadiri’s utopic first painting is long gone now, its lost foundations dwarfed by beach-front resorts. Amid exclusive yacht clubs and overpriced restaurants, the rocky stretch of the Dalieh of Raouché remains a place where fishermen live, families meet, and children learn to swim. Despite public access to the sea being enshrined in Lebanese law, the government has systematically sold Dalieh off for development—a mega-hotel is set to be designed on the site by Rem Koolhaas. The Dalieh Campaign, Public Works Studio and Temporary Art Platform have launched juridical, political, intellectual and creative challenges to this destruction, the latter taking the form of commissioned artist interventions along the coast. Ieva Saudargaité’s Thin White Line (2017) divided Dalieh in two with a 400-metre stroke of chalk. Derived from limestone, of the kind found on Dalieh’s rocky landscape and used in the construction industry to produce mortar, the line reflected the site’s legal designations: on one side, land protected from construction; one the other, land that can legally be built upon. Left to the mercy of the sea and rain, the line got bleached, blurred, washed away. Upset by the very elements its jurisdiction is meant to protect, the work revealed public space in Lebanon as inherently vulnerable, its erasure inevitable, and indelibly tied to speculative construction.

Local speculation maps visibly onto the art world, as Beirut’s small and resilient art scene—characterised by a richness of grassroots organisations established since the 1990s—finds its topology changed by a recent rash of private art foundations and large-scale museums. These exacerbate a stifling economic and political environment for the arts, in which funding is exhausted, and mobility limited. Crucially, therefore, at the core of Mansion’s financial model is the gift. The house is given to its community for free, low studio rents cover its running costs, and contribute to residencies and repairs. This gift, although temporary, relieves Mansion from the permanent precarity and unceasing labour of cyclical funding applications, and from the need to conform to narrow notions of institutional success. Remaining independent of art grant ideology, accountable instead to its users and community, keeps Mansion elastic, self-critical, and responsive to the immediacy of its social and political context.

As I write this, Mansion is going through change, an extended period of evaluating its work, questioning its purpose, speculating upon its future, consulting its community and proposing new modes of collectivity and governance. The owner could choose to sell his house next year. Such a scenario would be a significant loss, but I reckon it would also reveal Mansion for what it really is: not a building, but a network of people, who have treated collectivity as a practice, and trained that muscle in themselves. Work though it does for the protection of nature and heritage, Mansion’s greatest assets are arguably most fundamental to the future of nimble, critical cultural practice in Beirut: the space to fail, to change course, to grow with abandon, and to pull up your roots and set fire to them.

- Rachel Dedman