My Home is an Archive

Commissioned by The Mosaic Rooms, London, 2013. Published originally in four parts here.

1. My home is an archive.

Never have I lived anywhere so surrounded by stuff; messy, dusty, beautiful and seemingly endless.

My flat is up a small street through the car park opposite Geitawi hospital, in East Beirut. There are no formal domestic addresses in most of the country, and no way of getting post delivered. People develop modes of navigation around the city that rely on language rather than Googlemaps.

Pink bougainvillea pepper the houses opposite, and the flowers drop onto the ancient cars parked beneath. Cats curl up on the twisted cardboard that covers the windscreens. An enormous lemon tree dominates our front garden and extends up to the second floor. It gives the house its name, and us fresh lemons for most of the year, until we can no longer reach them from our balcony.

Inside is a time-warp.

In the living room, two sofas and four armchairs are upholstered in polyester-silk, patterned in a patchwork style with a recurring motif of tulips. The palette includes creams, greens and taupes; once bright, they are now greying and frayed. A low coffee table, glass-topped with four legs – only three of which touch the ground – sits in the corner. Made of dark wood, and chipped a little, it was probably considered chic in the 1960s. On top of it is an old-fashioned telephone, with a dial you rotate with your finger. Black, glossy, heavy; there is a number printed on browned paper and tucked into a slot on the front – 32.59.58. Against a wall squats a ‘Solid State All-Transistor Quick Start’ television, set into a faux-bois casing, gathering dust.

There are three pictures on the walls. One is a faux-Impressionist painting of a city and the banks of its river; Paris, perhaps. It sits in an ugly frame, once bronze, now dusty buttercup. On the opposite wall, in a burnished ornate surround, a portrait of a young boy standing contrapposto in a dark landscape. Someone has added a cigarette to his flaneur fingers in pen. To its left, a cheap print of a Chinese scroll painting of a chase or hunt. Its frame is metallic, the print trapped in the prickly embrace of a chipboard mount.

Two chandeliers of frosted glass are suspended from the ceiling. On the larger, the eight arms are connected by strings of glass pendants, some of which are shaped like daisies. A number are broken, dangling loosely, catching the light. Cobwebs grow between them. Five of twelve bulbs work, one is missing altogether. The bulbs are shaped like candle flames, their holders circled by little impasto plastic drips, neat rivulets of wax held eternally mid-melt.

In the study space that extends from the living room towards the back of the flat, a central desk is littered with objects, including a large clock in dark wood, with an undulating frame around a central face. The numbers are in an art deco font, slender and affectedly curved. It still works if you wind up the back, though the tick is unbearable.

On a sideboard, several souvenirs from foreign travel dot the dark shelves amid piles of DVDs and ancient coffee sets. These include the ultimate paradigm of touristic ephemera: a bottle of coloured sand poured to create an image of a camel in a vast red desert, above which floats the word Jordan. Gold plastic facsimiles of the main sites in Paris sit on a flat pink pedestal – the Eiffel Tower, Arc du Triomphe, Notre-Dame. There is a lumpen candle in the shape of a heart, and a tiny bust of Napoleon Bonaparte.

In an imposing armoire against the opposite wall, approximately 40 copies of La Revue du Liban, dating from 1985 until 1992, are stacked on the bottom shelf. Many covers feature huge colour photographs of military men from the course of the civil war, and occasionally a foreign president. On top of the pile is tucked a table lamp of salmon china, with a white central panel painted with flowers. The double cord is wrapped around its neck, and it lacks a bulb, though its lampshade – white papery parchment frilled with short silk trim – sits nearby.

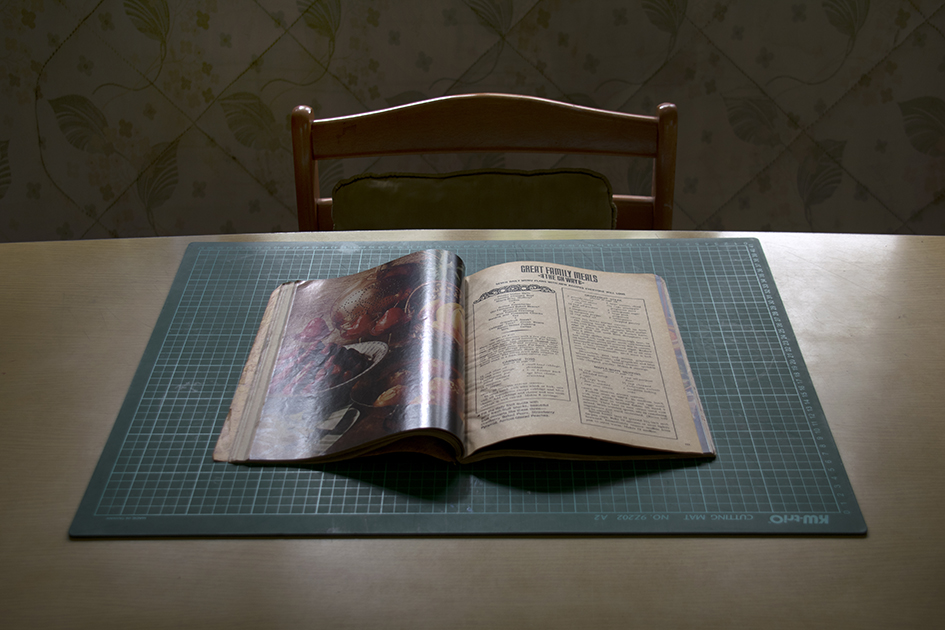

There are countless books here, but among them are twenty-one volumes of Collier’s Encyclopedia, in non-alphabetical order. The spines are blue and red, with gold lettering. By the same publishers, a set of ‘Junior Classics’ with titles such as Once Upon A Time and Call of Adventure. Predominant themes among novels are romance, whodunnit and science fiction, mostly published in the 1950s and 1960s. Titles include Pillow Talk by Marvin H. Albert from 1959, featuring soft-core sex-appeal caricatures of blond Americans on the cover; Reseau sous-marin by F.H. Ribes from 1965 – this cover features the word ESPIONNAGE emblazoned near a helicopter swooping over frothy ocean – and a collection of new French science fiction stories from 1968, the racy front designed by a Michel Desimon.

Near these are a host of children’s schoolbooks, for Maths, Geography, History, all in French. I find it strange here how demarcated education is along linguistic (and thus broader cultural) lines in Lebanon. Geitawi is a Christian area, where most people still speak French at home, even at the expense of Arabic. The books in the flat are in English, German, Arabic and Armenian, but the textbooks are all French, a relic of the impact of colonial history upon the academic and cultural development of Lebanese Christians, an influence still experienced today.

Picking up one of these books and idly flicking through it, I see a name in blue biro penned in the upper right-hand corner of the first page: Irma Guverdjinian. The book is called Le Francais – LIRE ECRIRE PARLER, a textbook designed for 6th grade children around 10 years old. The book is hard-backed and battered, the spine held together with tape. Printed in 1974, a fact betrayed by period typography as well as the publisher’s frank, the cover inexplicably features two elephants eating hay from the back of a red truck.

I had been living in the flat for many months at the point I found this book, and Irma’s name. I was of course aware, in that time, of the objects that filled the strange space of my home – whose décor and interior were a talking point with visitors – but I had not really thought much about them.

While I had considered these objects dusty novelties in my home, Irma’s book made me realise that, in actual fact, I am a guest in a space which has a long, rich history of its own. I became newly conscious of the things around me and the people once attached to them. A walk through the space felt like archaeology, peeling back layers of time – German magazines from the 1990s, newspapers from the 1980s, curtains from the 1970s, an AUB yearbook from the 1960s, letters from the 1950s. The flat contains multiple strata of time, but so jumbled together, so everywhere, that they aren’t really visible – until a name in a book tugs one layer free.

It struck me that this space, which my housemates and I inhabit as friends, was also for decades a family home. A home where children played and grew up, where teenagers studied for exams, where parents cooked meals and argued and did laundry and talked with their neighbours across the back courtyard.

The more I began to look, the more I spotted things that constituted relics of a family space. At the bottom of a book teaching Arithmetique Commerciale was the carefully printed name Robert Guverdjinian. Practice typing exercises – also Robert’s – slipped from the pages of an old notepad, his signature swirled at the bottom of pretend correspondence for a course in formal French composition. Other names appeared too, all Armenian, embroidered on blankets, scrawled in jotters, printed neatly in ancient birthday cards: Kasparian, Aintablian, Kradjian. The latter, Kradjian, is the surname of our landlord, Leo, who lives downstairs with his family still. This chimes with the palimpsestic nature of the flat’s contents; a space shared over the decades by aggregate branches of a large family, for cousins and aunts and other clans by marriage.

Looking at objects as clues, my housemate Sara and I began to speculate. Two large show-catalogues for German furniture, marked with notes and numbers in Arabic, suggested someone here was once a salesman – we flicked eagerly through both for a glimpse of the strange sofa-set that dominates our living room, but were disappointed. We trawled AUB yearbooks stashed in an old cabinet for mention of a Guverdjinian, scanning the rows of black-and-white ‘60s haircuts and cat-eye frames, our eyes catching at every Armenian surname, marked by the suffix –ian. Our imagination was set in play by the discovery of an incomplete California tax form for the year 1966; a postcard in German from friends abroad; by a self-help book entitled How to organize and sell a profitable real estate condominium. However eccentric and informal this archive – constituted of things left behind, of objects un-taken – it seemed to conjure up a powerful reflection of Beiruti life in the twentieth century: the multi-lingual, middle-class existence of the city’s Christian Armenians. In the books and china, a Franco-European influence is clear, though the practical administrative skills, export documents and foreign income forms indicate travel and connections to the USA.

Tens of thousands of Armenians came to Lebanon following the Armenian genocide in 1915, when millions were killed by the Turkish, expelled from their homeland, and forced to flee. They settled across the country, most in Bourj Hammoud, Beirut, near my home in Geitawi. By 1926 there were 75,000 Armenians in Lebanon, and the population was considered large enough to merit representation in parliament – which in Lebanon is divided strictly along confessional lines, supposedly representational of the country’s different religious demographics. Such a system lies at the root of Lebanon’s contemporary problems: sectarian in-fighting dominates the government, which is nowhere near representational today. Seats were originally assigned on the basis of a census in 1932, which – over 80 years later – is embarrassingly out of date. Another census hasn’t been taken since, for to do so would reveal the dramatic changes Beirut’s religious landscape has undergone, particularly the huge growth of Muslim populations – marginalised in the original parliamentary demarcation – and dramatically undermine the power of the Maronite and other Christian groups. Though integrated within Lebanon, Armenian life and culture is strong and distinct, particularly in Bourj Hammoud – brimming with restaurants, statuesque churches and the Armenian language. Haigazian University is an Armenian institution, located in Hamra, and one of the best in the country. Armenians attempted to stay neutral in Lebanon’s civil war (1975-1990), though the conflict reportedly fortified Armenians’ differentiation from other groups, and rigidified its ethnic boundaries.

The flat is a touchstone to such histories. Through its objects we have access to glimpses of lives and personalities, told through things left behind. We are not living in a blank space, after all, but in one filled and stretched and defined by previous inhabitants – their things most of all, but beneath those their tastes, their decisions, relationships and ideas. Who are they? Why did they leave? Where are they now?

2. My home is an archive.

In a cupboard off the side of the kitchen sits a tureen of sturdy white china, decorated with painted purple flowers and gold edging. One handle has broken off, and the swollen belly is stained in places. It comes with an set of dishes in a similar style. Lying prostrate behind another door is a soda shaker of glossy red enamel. Made by Sparklets of England in the 1950s, the brand’s name is embossed in the silver top. It is layered with dust, but forty-year-old soda still rolls around inside. I wonder if it would fizz if I opened it.

Dominating the room is an enormous, ancient beast of a refrigerator. Named the Kelvinator, the promise No Frost swirls jauntily across the freezer. The front is a yellow colour – once canary, now curdled milk. The handles are chrome, covered with dark leather. I could fit inside it.

The sink and work surfaces are cloudy grey marble. The latter are covered with spices and bottles of olive oil. The cupboards above them, lined with thinning paper and pasted with stickers of fruit – ubiquitous in the kitchens of old Beiruti homes – are filled with endless tiny cups for Turkish coffee. One set, of white enamel, features teeny handles patterned with flowers. On a low table by the door to the back balcony are three ceramic dishes shaped like crinkled leaves, in chipped yellow slip. The veins of the leaves are impressed into the bottom, where dust has collected. Miniature bunches of grapes and cherries, and little groups of nuts, are painted round its edges.

I love cooking in our kitchen today: adding olive oil to labneh for breakfast (the oil poured into old water bottles straight from a friend’s press), sprinkling zaatar over a hot cheese manouché, crushing garlic to add to thickly-stirred fava beans and chickpeas to make foul. Such foods are Lebanese staples, and I can’t help but think of their preparation in decades past in much the same way; of friends drinking the same coffee in the same cups, wine from the same glasses. Only perhaps Armenian favourites were also on the menu. My knowledge of Armenian cuisine is limited to outings to restaurants in Bourj Hammoud, but these have included bowls of itch, a kind of tabbouleh; kebab with sour cherries; basterma, cured beef; and – as those of my friends brave enough to try them attest – delicious fried baby sparrows.

The name Irma Guverdjinian continues to niggle at my mind. Google, however, yields absolutely no results for her full name, an apologetic error message appears instead. A search of Guverdjinian on its own, though, produces five. Most of these are irrelevant, but one hints at something fascinating. The first link that emerged from the depths of the internet was to an ancient-looking website called www.onefineart.com. Google had located a profile, in French, of an artist – Georges Guverdjinian, also known as Georges ‘Guv’. Quite lengthy and detailed, the article detailed Guv’s life and work.

Born in 1918 in Adana, Turkey, Georges Guverdjinian arrived in Lebanon in 1923, having only fortuitously escaped death in the massacre of Armenians and Greeks that occurred in Izmir the year before. He attended school in Achrafieh, and eventually studied at the Université de Saint Joseph. Guv was then among the first class at the Academic Libanaise de Beaux-Arts, Lebanon’s main art school, where he studied fine art, specialising in painting. The article goes on to describe his artistic philosophy – characterised by a sensitivity to human suffering – his approach, travel and various exhibitions. He showed his work all over Beirut, as well as in Europe. He received the Prix de Cinquantenaire du Génocide Arménien in 1965 and the Medaille de la Ville de Rome in 1972. He moved to France in the 1980s, where he continued to paint until his death.

I was intrigued. This name – Guverdjinian – utterly without Internet presence, had revealed an artist. And one who seemed fascinating and important. Was he related to Irma, to the family who once lived in my home? The name struck me as uncommon (according to Google it has vanished) so it seemed possible. Why could I find nothing else about the family? I take my search offline, scouring countless books for a mention of Georges Guverdjinian; mining art historical texts and artist dictionaries in Librarie Orientale and Librarie Antoine, in the bookshops of Hamra, and the bookshelves of Dawawine and Ashkal Alwan. Georges ‘Guv’ Guverdjinian seemed so interesting, so vital, and yet he appeared to leave little to history.

I email my friend Sarah at RectoVerso, an art library and research space in Monot, Beirut. I ask whether she knows anything about Georges Guverdjinian. She sends me back camera-phone snaps from an old French Index of Lebanese painters, with a small section on Guv. It reiterated the picture I was building from the article – of a thoughtful artist, a man “who sought to give form to his obsessions: the Armenian tragedy, and the suffering of the modern world”. I was aching to see images of his work.

A breakthrough came one day when searching for Georges Guverdjinian on Facebook. A fanpage exists, for an artist called GUV, whose introduction confirms this is the same man. The page also yields crucial information: ‘Guverdjinian’ can also be spelled ‘Koukerjinian’. This detail feels like finding treasure. Whereas Irma Guverdjinian had no web presence, the name Irma Koukerjinian gets hundreds of hits, and I begin to plunder the web for mention of others in the family.

The original article about Guv mentioned children – Francois, Arlette and Roger – so these I seek, along with Robert and Irma. I find reference them all, and begin to piece together a shaky family tree from the surface of the Internet – they are certainly related to Georges Guv. It seems that most of the family live abroad now, in the US and France predominantly. According to public census information Robert moved his family to California (corroborated by those tax forms), and then to Virginia. Irma is now a grown woman, whose profile picture on Facebook shows her smiling with flowers behind large sunglasses in Summer.

I begin to get in touch. What would their memories be of this space? Why did they change their name? Why did they leave Beirut? Can they tell me more about Guv?

Placing some stuff in a storage cupboard above the bathroom one day, I find a bag full of old children’s toys – an eerie remnant of past play. I pull out a 4x4 truck covered in small stickers, with orange headlights and large rear tyres. Inside a driver with a racing helmet sits behind the wheel. The words WILD WILLY are emblazoned on the back bumper. Though the toy is old, the brand still exists – there is a toyshop in Hamra with the same name. A doll with blonde straw for hair, and creepy soft-lashed eyes, appears stiff-limbed in a red dress and apron. A bedraggled bear with ears whose fur has rubbed away follows her. Such toys, which must sit, near-identical, in the attics of most families the world over, recall again the children who once played in the house – a memory reinforced by the ancient decals affixed to my bedroom window, of teddy bears catching butterflies in swinging nets.

I’m sitting on my bed, head resting against the same window, when my Facebook email pings. I had messaged the inbox associated with the GUV Facebook fanpage, and have just received a reply – from Arlette Koukerjinian, Guv’s daughter! In polite and effusive French, she tells me how thrilled she is to hear from someone interested in the work of her father, and is happy to answer my questions.

So begins our correspondence. Arlette explains that when the family translated their name from Arabic into French, the spelling shifted to Koukerjinian. She had moved to France to escape the Lebanese civil war, and her parents followed in 1982, remaining in Paris until Guv’s death in 1990. She also tells me that after Guv’s death his work was distributed among members of the family, and I finally access some images on the Facebook page. They are all simple photographs snapped shakily on a little camera, and presumably only of those pieces to which Arlette has access. The variety is striking: half are figurative, semi-surreal images in pen, of willowy lack-limbed female forms standing, inert, in ambiguous landscape. The other half are vibrant colour-fields, near-psychadelic in intensity, concerned with the physicality of paint.

One of the former drawings shows an elongated female nude, an armless Modigliani, half-obscured from us by the spindly, bare tendrils of a tree. Our gaze follows hers, turned towards the sun. Or is it the moon? The scene is built up by tiny pen-pricks, growing in density towards areas of dusky depth, spare and flickered in the light. The orb she gazes at appears bright and sun-like, but is formed from the negative space of the page. Like an optical illusion, the mind flicks the shape from sun to moon, day to night, while the ambiguous landscape gives nothing else away – writhing forms indicate the flora of hillside, but of ultimately unscaleable distance.

Such long female subjects appear to haunt Guv’s paintings too, which plunge these spindly forms into liquid seas of paint. In one, the rich expanse of deep purple background is broken by bubbling yellow semi-figures that rise up at the surface, a stark forest of stripped trees through which one might wade. The thick oil paint has blistered and cracked, forming welts on the canvas. Another, this time in gouache, wraps its spindly human forms in layers of thin slip, colour bleeding into the spaces between Guv’s pen. The figures, always multiple, though never connected, appear to loom from the watery surface.

I have almost no information about these images, uploaded naked to Facebook. I don’t know their titles or their dates, the context of their creation. Something about them tells me they are sketches, experiments, the in-betweens on the way to finished pieces. My desire to see some complete ones, shiny and framed, dissipates. I realise that these works resonate, somehow, with the stuff of the flat; the books and the toys, the souvenirs and old letters: the intimate, liminal stuff that sits between the things you discard and the things you take with you. These images, fuzzy and distorted, seem suddenly to reflect this whole endeavour. My attempts to know Guv can only ever be partial, in the same manner I meet these images – filtered through decades, passed through the Internet, flattened by pixels.

3. My home is an archive.

I am rifling through a stack of ancient newspapers one day, when I receive a call. The magazine I am reading – Burda – is typical of the kind scattered across Lemontree House, a German fashion magazine from the 1960s. Inside, shiny-haired ladies with pointed shoes smile in knitted bathing suits and longline cardigans over kicky A-line skirts. Such periodicals come with sewing patterns so women might make the clothes they see within. To save space, multiple patterns are layered together on one sheet, numbered and coloured so the reader can distinguish between them. These featherlight papers resemble beautiful maps of strange waters, utterly unnavigable.

The woman on the phone is Christine Zacharias, who works at ALBA – the Academie Libanaise de Beaux Arts – to whom I had submitted a message online enquiring about Georges Guverdjinian, having discovered he was both a student and professor there. The school’s website only had a standardised online form to submit queries, and I hadn’t expected a reply. Christine had seen it, however, and got in touch – she and her husband had been taught by Guv, and her mother-in-law knew him too; she even had one of his aquarelles on her wall. Above all, Christine recommended I speak to Harout Torossian, an artist and good friend of Guv – they taught together at ALBA.

On a hot day about a week later, I meet Harout in ALBA’s outdoor café, where we sit and talk in the breezeless shade. Harout is an artist’s artist. All white hair, jaunty hat and gentlemanly French demeanour; he kisses my hand when we are introduced. He speaks no English, nor Arabic, issuing from an era where an Armenian-French hybrid was all you needed in Beirut; for many it still is, though most young people now speak English too.

At 80 years old, Harout is still a charmer, and a very successful painter; I had recognised his name from posters advertising a big retrospective exhibition a few months previously. He laughs in cheeky conspiratorial cackles. Based between Lebanon and Paris, when he is in Beirut he keeps a studio and flat in Bourj Hammoud, where he is currently painting a huge two-metre canvas of Adam and Eve, a private commission. The nude, the body – these are Torossian’s real loves. He makes me a gift of a recent monograph, a blue book filled with essays from other artists and friends, images of his paintings, and pages of photographs collaged together – of Harout and his pals, his family, other art bigwigs, and (he points out with great pride) the President of Lebanon. His paintings are gorgeous, constructing the body from a combination of brushstroke and the inherent texture of paint; academic, but with something vital captured too.

I ask him what it was like to be an artist in Beirut in the twentieth century. Before the civil war, he tells me, it was calm. There was a market for art, though not a great one, but if you had an exhibition, you would sell. Once the war started, many artists travelled abroad, emigrating to Europe. Harout stayed, and describes a strange equilibrium to his experience of the conflict – if there was a bomb here, there was a bomb there – referring to the split down Beirut’s Green Line between the city’s East and West. He confirms it was dangerous, every walk in the street might meet with an explosion; a remnant of the conflict that continues today, as bombs still rattle Dahiya, Beirut’s Southern suburbs, in the week we meet.

Harout trained as an artist in France initially, before returning to Lebanon to join ALBA in the third year they accepted students; Georges Guv was among the very first generation at the school. Harout confirms a few physical details about Guv I had gathered from the one small photograph I’d seen. Of mid-height, with brown-grey hair and a clean-shaven chin, Harout tells me Guv was a principled man, always polite, “and very loyal to his wife, extremely loyal”. Guv’s entry in the Index of Painters suggests he did not spend much time in the social scene that swirled around ALBA, an artist without any of the arrogance or pride a celebrated painter might have had then. As well as teaching undergraduates at ALBA in an academic manner (drawing, charcoal, oil painting), he also taught art to younger children, in an Armenian school whose name Harout could not recall. From the Index I had also learned that Guv served in the Lebanese Association for Tobbaconists, as “fonctionnaire a la Regie Libanaise des Tabacs et Tombacs” and ran a papeterie alongside his ALBA teaching.

Georges Guv, it seems, was in many ways an ordinary man, but one with an extraordinary depth of feeling. The person who left his tobacco post and stationery shop, who came home to his wife and children each night, was deeply affected by the problems of the world. Harout tells me that Guv felt keenly the suffering of humanity; and his painted forms were lively until catastrophe struck, when he would abandon colour. Harout describes Guv’s paintings from the civil war: using greys and dark tones, Guv enclosed his canvasses within a thin skein, stuck to the still-wet paint, this sticky shield closed a curtain on their darkness. These resonate with the drawings I’d seen, the spindly, armless forms floating in monochrome landscape, staring at something beyond the frame; imbued with a loneliness or melancholy.

This also chimed with what I had been gathering from Arlette, who was recounting in our email correspondence the full histories of her family. She described the difficult journeys her grandparents (Guv’s mother and father) undertook to Lebanon. In the great massacre of Armenians at Izmir, the family all miraculously survived, but were split from one another. The children – Guv, aged 3, and his sister, aged 6 – found themselves bundled onto a boat bound for a Greek island, while their mother was placed on a ship to Beirut. Their father was captured by the Turks, a lucky fate since the vast majority were slaughtered, but it was two years before he could escape and make his way to Lebanon. Here, with the help of his wife and an uncle who lived in Martyrs Square, they located the children, still living in Greece, and brought them to the city to join them.

The story of Guv’s journey to Beirut resonated powerfully with the images I had seen of his work. Having to flee a flaming city to Greece, aged only three, with no-one but his six year-old sister, must have been a traumatic and terrifying experience. Living there without either parent for two years, perhaps as isolated by language as by the unknown fate of his family, the lack-limbed female figures in his ambiguous drawings take on new potency. One can’t help but understand reports of his heightened compassion and sensitivity to suffering in terms of his harrowing early years, and imagine the amputated women as lingering emblem of separation from his mother. Witnessing the horrors of the civil war in Lebanon, decades later, must have been particularly haunting.

A generation on, Guv’s daughter Arlette remembers a peaceful and prosperous childhood growing up in Beirut, first in Geitawi, then in Gemmayze, a neighbourhood nearby. The children encountered no racism as a result of their Armenian heritage, though they were teased for their sub-standard Arabic, speaking nothing but French at home. Guv had exhibitions, television interviews, articles, and travelled all over the world. In 1975, however, the civil war changed a great deal. Arlette tells me that by this time she was living in New Jdeideh, a district outside Beirut, to the North, with two small children of her own. All of the close family who lived in dangerous zones in the city would come to stay with them to escape gunfire and bombings. They lived precariously, with little water and even less electricity, taking shelter with their children in the dirty basement of the apartment block, full of rats. Around a year into the war, a bomb fell onto their building, destroying the majority. The family had been out at the time, but this close call was the final straw for Arlette, who then hurriedly moved her family to Paris, where her brother Francois had relocated his young family just a few months before. Her parents, Guv and Marie-Jeanne, would stay in Beirut another 6 years, moving to Paris in 1982. Under such circumstances, one can imagine the lack of need, if not opportunity, to sell one’s home. After luggage is packed the house is shut up, all but the essentials left within, locked with fervent promises to return one day.

4. My home is an archive.

The search for Guv feels far from over; Harout has passed me the phone numbers of all sorts of interesting people – the Curator at the Sursock Palace Museum in Beirut, which should have Guv’s works in their collection; other Professors at ALBA who worked alongside Guv himself; friends and neighbours who lived near him, who hang his paintings on their walls.

At a party in Lemontree House one night I relate to a stranger a little of this story, and reflect on how simply it started: with a name in a book from 1974. This project, which had an unambitious premise – to take the flat as a catalyst for thinking about Beirut – grew into something beyond the space, into correspondence, friendships, glimpses of history, of art history.

Guv had married a woman named Marie-Jeanne, while his brother Jacques married her sister Victoria. Arlette, my now-treasured correspondant, is therefore cousined to Jacques and Victoria’s son Robert twice over. It was Robert’s family, Arlette finally confirms from photos, who once lived in Lemontree House.

Reflecting once more upon the space, I became aware of my own contribution to its latest layer of life. In its current iteration, Lemontree House is representative of one kind of existence in Beirut – a home for twenty-something internationals renting for a few years at a time, in Lebanon for work or study. Just as previous occupants deserted their yearbooks and crockery, we will leave our marks upon the space in turn, in the form of boxes of pirated DVDs in their perennial plastic packets; in the three hundred-strong army of empty beer bottles on the back balcony, (a permanent installation, increasingly rain-spackled); in the irons and hair dryers and insect repellent devices – the electrical ephemera abandoned when airline baggage allowances strain resources.

Previous housemates have left their presence in strange but artful collages on the living room ceiling, in the peeling notes on the fridge and the football stickers pasted to the oven. No-one can remember quite how the large-scale cut-outs of Captain Haddock and Snowy the Dog made their way into the apartment, or whatever happened to Tintin. These things too constitute a layer of archaeological history, a generation of objects, that may – in thirty years – be curiosities themselves.

I sit on our ugly sofa, my feet on the low table in the centre of our living room, made from a wooden pallet. It is marked with paint, pen and burns from cigarettes, and sprawled with books, half-drunk coffee cups and discarded football cards – my flatmate Tom is collecting them for the World Cup. Motes of dust float in the half-light, which shimmers off a square ashtray, of translucent orange glass, tilted on the window sill.

In a corner of the living room, behind the television, sits a small faux-Christmas tree, flaunting its dulled lights all year long, tarted up around December. The paintings on the walls wear boas of yellow and black, whose feathers which float in the hot summer breeze of our industrial-size fan. The mild smell of burning incense issues from ubiquitous coils of green Vape, which smoulder slowly overnight to repel mosquitoes. Each day starts with emptying neat curls of ash into the bin.

Summer takes its toll on resources in Lebanon, and at the moment Beirut is subject to serious water shortages, as well as daily unscheduled power cuts. Sara has stuck long candles in old Almaza beers, which allow us to cook and get to bed when the lights are dead. Their flames flicker against the bottles’ thick green glass.

This stuff will constitute, as much as the Guverdjinians’, our left-behind, our untaken, and operate as a record of time. Such material feels uniquely articulate, in that it carries little immediate value beyond the nostalgic. Nothing is really worth anything – the richness of such an archive is located somewhere beyond the objects themselves. They constitute fragments of history, threads escaping from a frayed hem, fallen free from the densely woven mass of past, waiting to be tugged at.

Such things record time like soft layers of tissue paper occupy space. In thin sheets – translucent and frail – that waft over one another; overlapping, but never opaque.

- Rachel Dedman