An introduction to War Rugs

Commissioned by MacGuffin Magazine for their issue on The Rug, 2020.

War rugs are undeniably compelling objects. Many look, at first glance, like traditional Oriental carpets: richly-coloured and studded with geometric patterns. A second look confounds expectations—motifs of rural life are supplanted or surrounded by guns and grenades, tanks and warplanes, maps and mujahideen. The main producers of hand-woven rugs in Afghanistan are the Baluchi (Baloch) and Turkoman (Turkmen) tribes. Although motifs of military vehicles appeared in their weavings as early as the 1930s, war rugs as we know them today were mostly made from the 1970s onwards; the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan was one clear catalyst. In the ensuing conflict, millions of Afghan civilians were displaced from their homes, internally or into refugee camps in Iran and Pakistan, where weaving continued and evolved.

It feels natural to think of war rugs as a form of resistance to circumstance, or implicit political critique. Weaving was predominantly practiced by women in modest, domestic contexts, and the motifs deployed in traditional crafts reflected local identity and lived experience. As the effects of conflict made themselves felt in every corner of Afghanistan, weaving was arguably a quiet but powerful outlet for the documentation of this reality, and a reflection of resilience. There is, however, an unfortunate paucity of research undertaken from the weavers’ perspective.

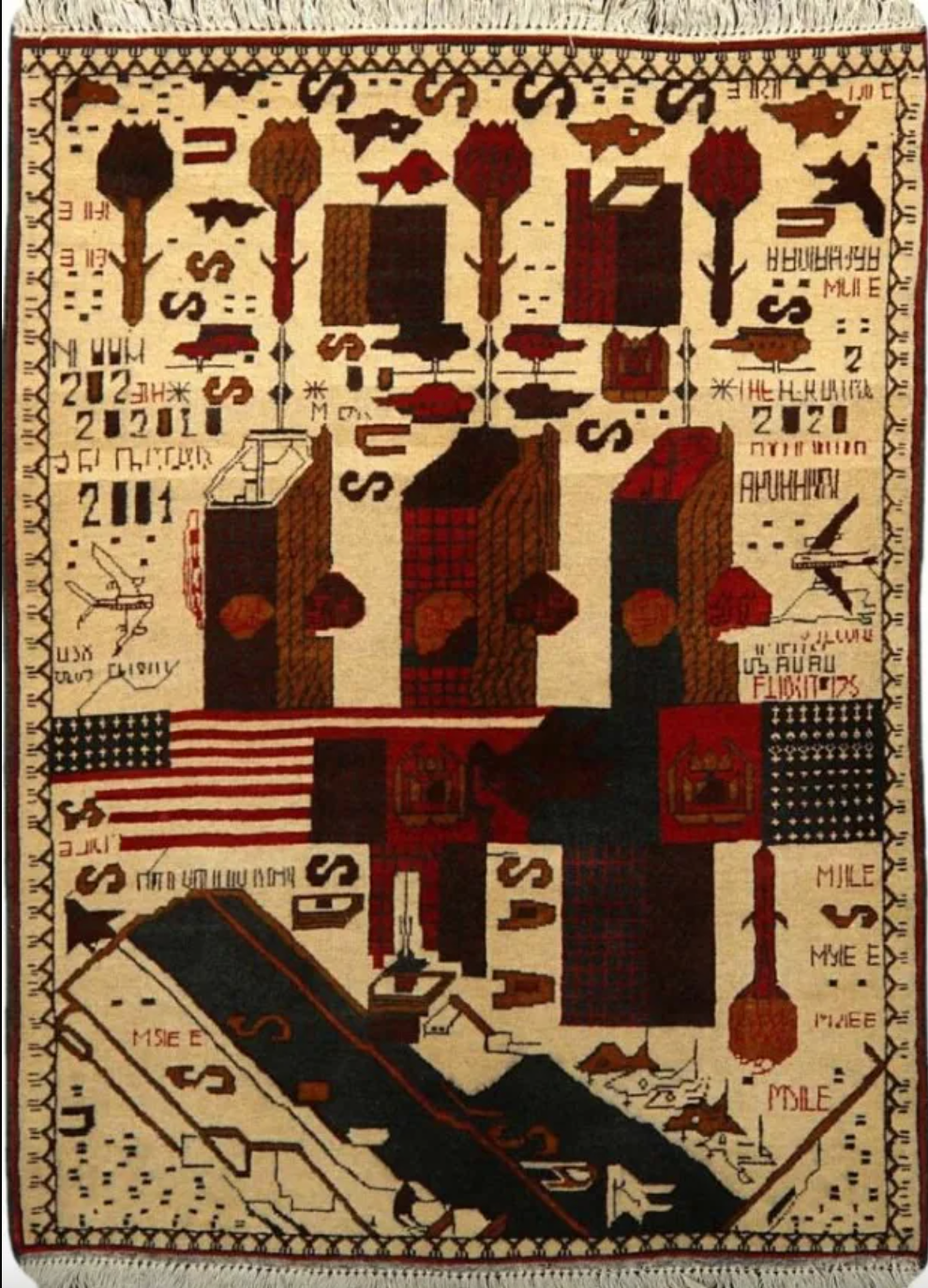

Much of the discourse around war rugs concerns their relationship to the market. Early war rugs, when not used at home, were likely made for Soviet tourists. With the arrival of the US military in 2001, war rugs became popular souvenirs among American soldiers, and designs evolved to appeal to their tastes. Art historian Nigel Lendon charts the evolution of a 9/11 memorial war rug. Unlike symmetrical formats featuring repeated patterns, the 9/11 rug operates as narrative picture. It depicts the planes crashing into the Twin Towers with the words ‘First Impact’ and ‘Second Impact’ knotted into the carpet, along with the United flight number, date and descriptions of place. Across the towers run the US and Afghan flags, connected via a white dove, separating the attack itself from the lower half of the image. Below we see fighter planes leaving US missile bases, presumably destined for Al-Qaeda strongholds. The genesis of the war—on Afghanistan and on Terror—is laid out like theatre.

Lendon describes how, as the design became popular, hundreds, perhaps thousands of such rugs were reproduced in the regions north of Kabul. These were made by hand, by men, in factory-like conditions: “the weaver would finish one, roll down six inches, and start the next one, in what was probably the most exploitative of circumstances.”[1] As the design was copied and miscopied, it evolved like a game of Telephone, eventually to the point of abstraction. In later versions three towers appear, the flags melt into one another, the text devolves into illegibility. The market has transformed production, and as repeated motifs return in the negative space, the narrative rug becomes pattern once more.

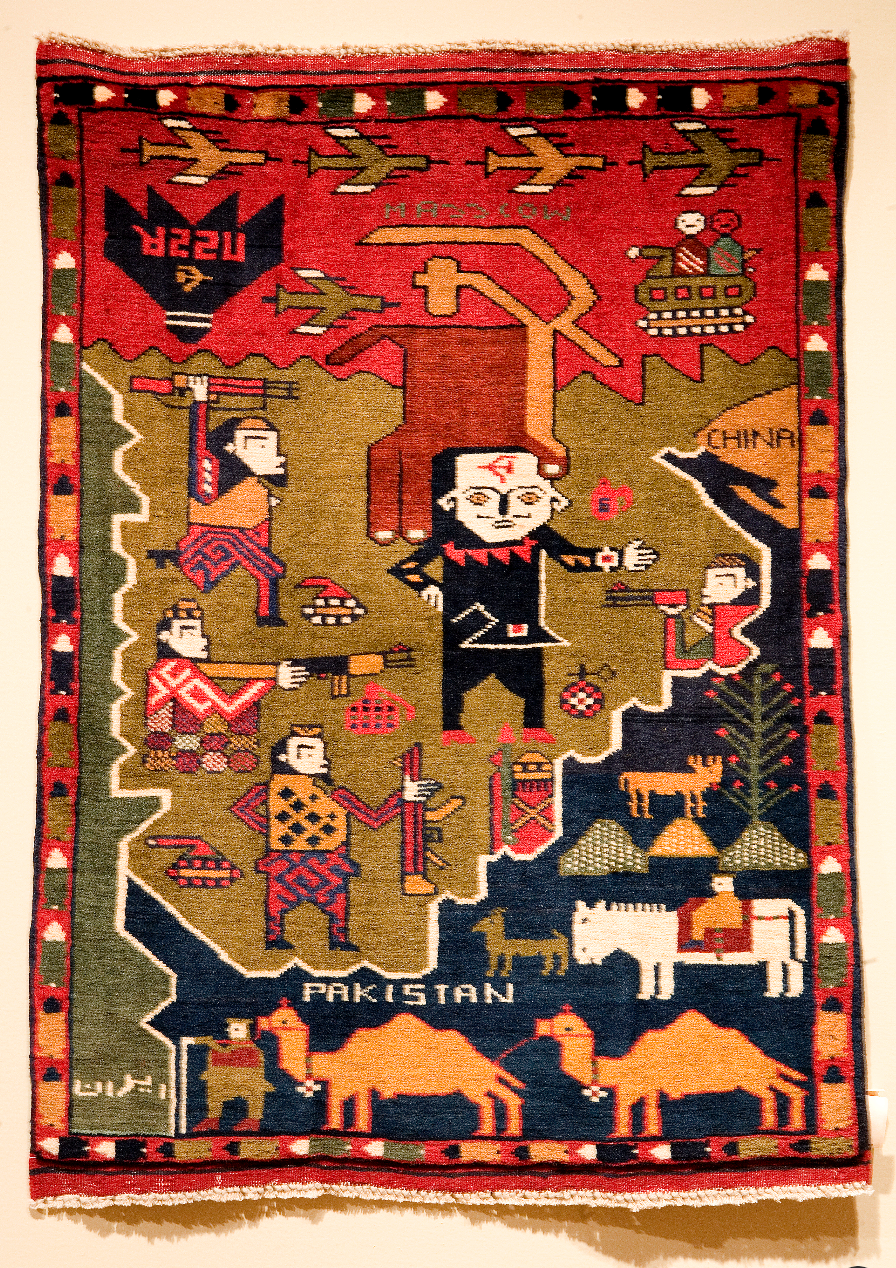

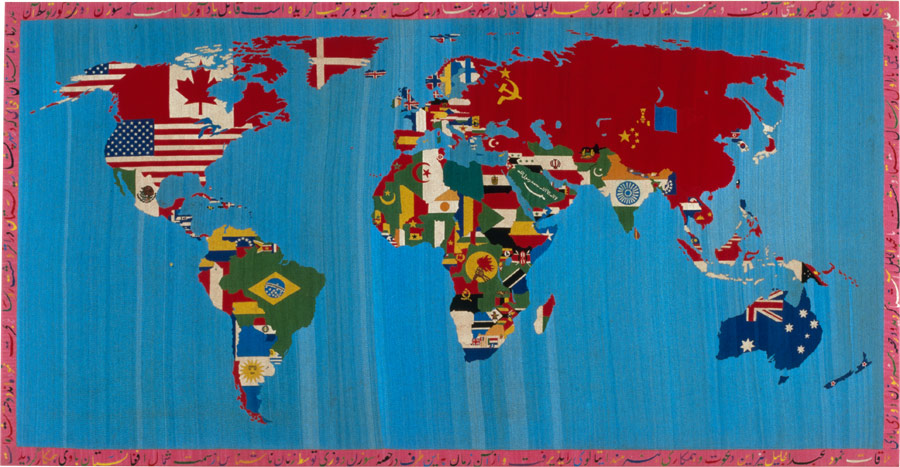

The very term ‘war rug’ is a sweeping one; art historians, collectors and dealers often order war rugs into loose categories. The website warrugs.com advertises its available stock under headings such as ‘Blue Subtle’ and ‘Overt Weapons’. Other types in its index include the ‘Ten Tank’ style, apparently from the region of Mazar e-Sharif, which commemorates Afghans’ victory over the Soviets; ‘map’ rugs, which some argue were inspired by artist Alighiero e Boetti, whose Maps of the World tapestries were commissioned from Afghani weavers from the 1970s onwards; and ‘Najibullah’ war rugs, a format reflecting the events of 1991-1993, when the Soviets installed a puppet government. The leader, Najibullah, is often depicted literally as a puppet, with a disembodied hand guiding his shoulders and a hammer and sickle woven into his forehead.

War rugs are deserving of closer scrutiny and further academic work from a range of perspectives—not least their makers’. The term encompasses a wealth of styles and formats, decades of political change, and carpets vastly different from one another. Not merely compelling, they are also complex. A war rug may be an expression of resistance, a market-driven souvenir, and a reflection of political change—sometimes all three at once.

[1] Nigel Lendon, ‘How to Read a War Carpet’, Reading the Pictures, 22 October 2010, https://www.readingthepictures.org/2010/10/how-to-read-a-war-carpet/ Accessed September 2020.